It’s interesting how cemeteries are lost over time. They are often family or community burial grounds located outside the main portion of the city. As time marches on, the land is taken back by Mother Nature and the cemetery is forgotten.

Until it's time to build a subdivision.

In case you're wondering, a developer cannot just simply continue building when a potential cemetery is discovered. In 1992, Louisiana passed the Unmarked Human Burial Sites Preservation Act.

"The legislature finds that existing state laws do not provide for the adequate protection of unmarked burial sites and of human skeletal remains and burial artifacts in such sites. As a result, there is a real and growing threat to the safety and sanctity of unmarked burial sites, both from economic development of the land and from persons engaged for personal or financial gain in the mining of prehistoric and historic Indian, pioneer, and Civil War and other soldiers' burial sites. Therefore, there is an immediate need for legislation to protect the burial sites of these earlier residents of Louisiana from desecration and to enable the proper archaeological investigation and study when disturbance of a burial site is necessary or desirable. The legislature intends that this Chapter shall assure that all human burial sites shall be accorded equal treatment, protection, and respect for human dignity."

The Highland Road Cemetery is the oldest known cemetery in Baton Rouge and was partially rediscovered due to a new development. Today it’s located smack dab in the middle of College Town Subdivision. In fact, at least a couple of houses are located on the known cemetery grounds, and there's a playground located directly next to it.

Oldest Cemetery in Baton Rouge

According to Historic Highland Cemetery, Inc., the nonprofit organization now charged with its upkeep, the cemetery boasts three of the earliest documented burials in Baton Rouge. The first known burial was that of John Hames Neilson on March 13, 1813.

At the time, the land was owned by George Garig, a German settler from Maryland who came to the area around the American Revolution. He purchased the plantation from Philip Hickey in 1794 and lived there until he died in 1825. He's said to be buried in the cemetery, but no marker has been found...yet.

At the time of those first burials, the area was composed of early settlers who were awarded land grants by the Spanish. The land was the natural bluff along the edge of the Mississippi River Flood plain, so this was known as the "highland." Because the land didn't flood, Garig allowed the community to bury people there.

We learned a lot about what life was like at that time when the Favrot papers were published and later translated into English. It was a collection of family records that went back to 1695, when a member of the Favrot family accompanied Bienville on an exploratory trip.

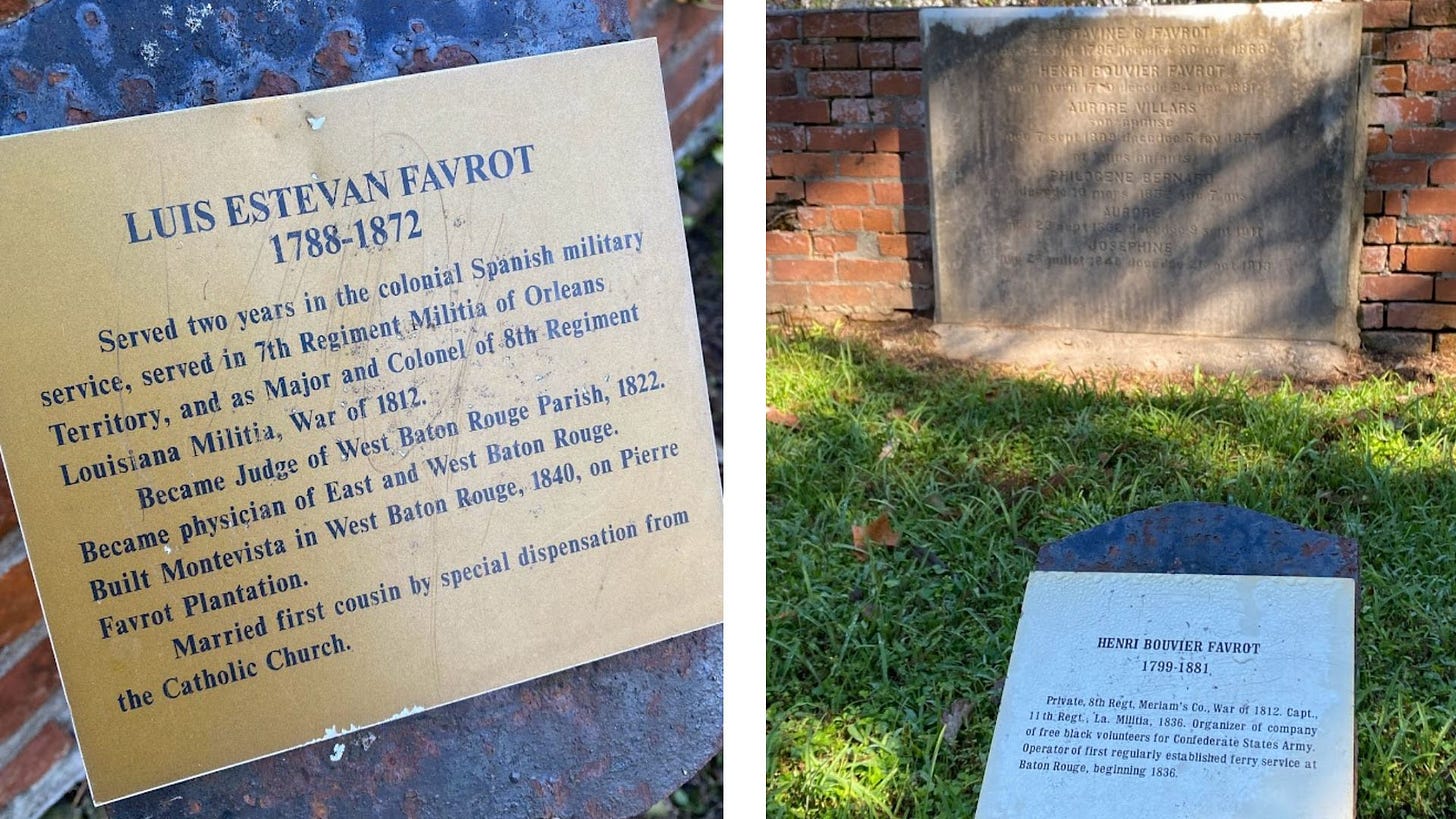

Much of the Favrot family is buried in the Highland Road Cemetery, including Octavine Favrot, who is the last known burial. She was 91 years old when she died and was buried on Feb. 25, 1939.

Lost Over Time

In 1819, the cemetery was donated to St. Joseph Church located in what is now downtown Baton Rouge. That made the cemetery "legal." The church had its own cemetery in town, but the clergy were officially charged with the duty of keeping up with the Highland Road location as well.

In 1840, the lower portion of the land was bought by Robert Penny. Funeral notices for the cemetery used to read "Penny Graveyard," and it was the name used by residents in the area for decades to come.

After the Civil War, the cemetery was largely abandoned. What wasn't destroyed by trees or vegetation was looted by grave robbers.

Over the following decades, the cemetery exchanged hands a few times before being sold to Pelican Realty Co. in 1923. The company hired A.C. Mundinger, a civil engineer, to survey the property and lay out College Town subdivision. It was during this process that a clerical error was made, which eventually resulted in two houses being built on property that was originally part of the cemetery.

The cemetery was restored a bit in the 1930s. But as the neighborhood grew around it, it began to get neglected again. In the late 1960s, Evelyn Thom decided to take a walk through the neighborhood. She was visiting her husband's parents, who had a home nearby.

The cemetery was overgrown, but there was something visibly there. She was curious about it, so she said she "brought my clippers out to get this stone and that stone. What I found was a resurrection of history, the history of Baton Rouge, the pioneers."

In an article published in The Advocate on April 27, 1973, she called the cemetery "one of the few remaining visual contacts with the past which can serve as a tool for the retelling of local history."

She fought to have it restored by the American Revolution Bicentennial Commission. The request was initially denied. Thom, her husband, and volunteers began restoration independently.

When working on the restoration, they discovered that many of the gravestones had been removed and pushed into a pile at the back of the cemetery. Through painstaking efforts, many of those markers were restored to their rightful place. However, so many markers and plots were lost.

They were later granted $7,000 from the Bicentennial Post for the remaining restoration needs. Much of those funds were used to build the large, wrought-iron gazebo in the center of the cemetery.

"We thought there should be some memorial to those whose graves are forever gone," Thom said in an article published in the June 23, 2003 edition of The Advocate. "We thought there should be some focal point."

It was officially dedicated on Nov. 1, 1976.

Thom, with the help of the Highland Cemetery board, kept the cemetery in shape for the remainder of her life. She passed away in 2011 at the age of 91. She is buried in the Roselawn Cemetery.

Bringing Back the Dead

In 2003, a ground-penetrating radar scan was conducted by a team led by Old Miss archaeologist, Jay Johnson. Several suspected burials and shallow targets were identified.

A systematic probe was later conducted. The process is more detailed and resulted in the identification of roughly 180 burial shafts within the current boundaries of the cemetery.

Other techniques have been utilized without success.

Excavations have also been conducted, and some interesting findings were made. And the search continues under the direction of the Historic Highland Cemetery Board.

Today, Kenneth Kleinpeter, a longtime board member, is the cemetery sexton, which means he is responsible for the preservation and treatment of the site. He helps coordinate any efforts to identify or locate remaining markers.

Our Next Ride

This was the first location in our October tour of historic cemeteries. Our next stop will be at the Lutheran Cemetery in Old South Baton Rouge. Where the Highland Road Cemetery tells the story of the early white settlers of Baton Rouge, the Lutheran Cemetery tells the post-Civil War story of the city’s Black residents.

We meet every Monday at 6 p.m. at the Electric Depot. The ride is free and open to the public, but you have to provide your own bike. Legally, you are only required to have a front and rear taillight.

Sources used in this article:

Articles published in The Advocate were accessed by the Digital Library, which is a service offered by the East Baton Rouge Parish Library System.

I always enjoy your history lesson on BR. This one was excellent, and interesting to learn. Hope to be able to join your ride someday.